- HOME

- RECENT WORK [2017-2024]

- SELECTED WORK [1980-2016]

- EXHIBITIONS

- 2019 | Over and all around

- 2017 | No.1 Around

- 2017 | Shapeshifting

- 2013 | Stolen Feathers

- 2012 | Chronotopology

- 2009 | Home

- 2009 | Being(s) Here

- 2009 | Laugavegurinn

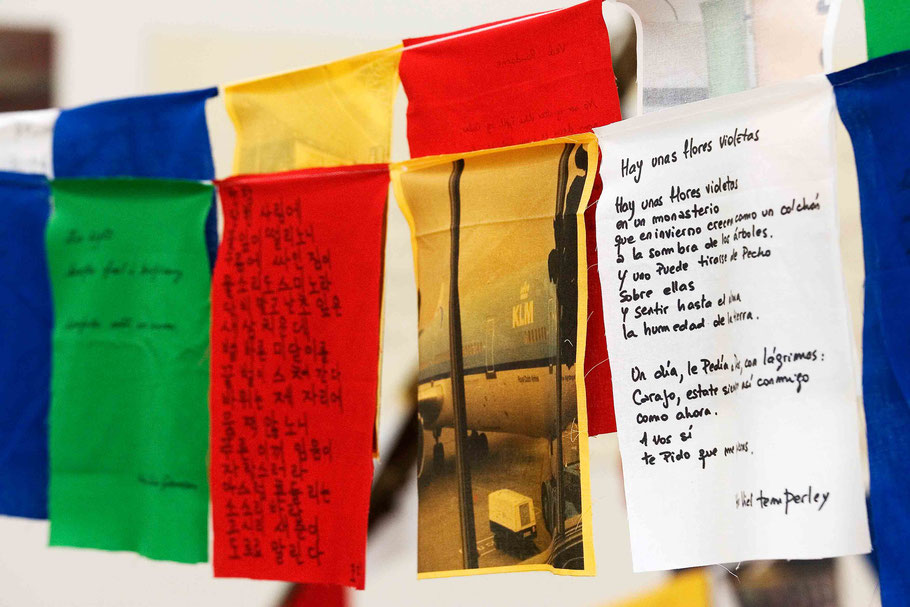

- 2007 | The Provincialists

- 2006 | Mega Vott

- 2006 | Footprints On The Galaxy

- 2005 | Storyline

- 2005 | Dream Feathers

- 2004 | Figments

- 1998 | Washing – Cleansing

- 1997 | Leaders Summit

- 1997 | Plates of History

- 1994 | Signs

- 1994 | Sculpture, Sculpture, Sculpture

- 1993 | Tree artist show

- 1991 | Untitled

- OUTDOOR

- INFORMATION

Into The Blue | The Provincialists, Gerdarsafn - Kopavogur Art Museum, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2007

Þórdís’s work is a kind of poetry. Like much of recent Icelandic poetry, it is full of everyday life and work and familiar, everyday objects. Not that she simply lifts the everyday objects out of their context and presents them as art--à la Duchamp. Often she crafts her objects from scratch, makes entirely new things, and when she uses recognizable ordinary things, a rusty old shovel blade, for instance, they are either modified or appear as parts of a larger work. Thus, they acquire a new nature.

Certain themes and ideas appear singly or in combination in much of Þórdís’s work: one such theme is the use of opposites, perhaps most notoriously that of hard and soft. Another is winding and wound objects: e.g. a thread of a delicate material, silk perhaps, wound around a rusty old iron object so as almost to cover it—an instance of hard and soft too, of course. A third theme has to do with Time and Nature as collaborators who transform things—an activity that may also be seen as Nature’s self-healing activity.

Even when there is an environmentalist statement statement in Þórdís’s work, I never have the feeling that she sees

Nature as seriously threatened. Her faith in mother Nature is far too strong for that. Even when she makes use of unmodified old junk, Þórdís is a superb craftsman: Her art is thoroughly thought through and leaves nothing to chance; it is made with an unerring, delicate sense for form, colour and material. The result is that her world of familiar, everyday things, transformed and placed in a new setting, evokes in the spectator a peculiar mixture of feelings: there is that of old familiarity and at the same time that of surprise and strangeness at the transformation of the ordinary.

The strangeness is not just strangeness for strangeness’s sake. The exact way in which Þórdís’s things are transformed has a symbolic dimension, actually often a double symbolic function: there is a reference to the outer world: to the ordinary function of the objects, to the environment, or whatever the subject might be. At the same time it is hard to escape the thought that, as in many a powerful poem, there is also a reference to the psyche, that her transformations express moods, tensions, obsessions. All this, however, is skillfully made non-obvious, alluded to rather than cried out.

Eyjólfur Kjalar Emilsson

Det at være overbevist om at jeg lever en tilværelse i et enormt, kolossalt, ubegrænseligt, cosmic rum (space / reality) og at være fuldstændig klar over at jeg er ligeså meget en celle som et menneske på to ben som trækker vejret, tenker, taler og ler sammen med dem jeg deler dette cosmiske rum / sted, med er og har været normalt i mine tanker ligefra engang i barndommstiden. Jeg husker mig som barn, löbende frit om i grasset på store endelöse marker også liggende ned på jorden stirrende op i himmelen enten op til en lys sommernat eller ind i den mörke, men lysende, stjernenat om vinteren. Det var på en gård i Syd-Island. Måske har denne fölesle for evighed og endelöshed let ved at komme frem netop i barndommen og netop i det bare, öde Island. Vi kan se så langt på afstand, fordi det findes næppe træer i landet som stopper udsikt, og det er næppe nogetsom hindrer det at man også kan se langt ud til havet. Det er fjerne fjæld og glaciers som man altid længedes efter at komme op på og se hvad det var at se, på den anden side. Og det er heller ikke folksmængder man möder for indbyggere er så få på den store ö.

Livet er en rejse for os og vi blander vores rejser sammen hele tiden både lange og korte.

Þórdís Alda Sigurðardóttir