- HOME

- RECENT WORK [2017-2024]

- SELECTED WORK [1980-2016]

- EXHIBITIONS

- 2019 | Over and all around

- 2017 | No.1 Around

- 2017 | Shapeshifting

- 2013 | Stolen Feathers

- 2012 | Chronotopology

- 2009 | Home

- 2009 | Being(s) Here

- 2009 | Laugavegurinn

- 2007 | The Provincialists

- 2006 | Mega Vott

- 2006 | Footprints On The Galaxy

- 2005 | Storyline

- 2005 | Dream Feathers

- 2004 | Figments

- 1998 | Washing – Cleansing

- 1997 | Leaders Summit

- 1997 | Plates of History

- 1994 | Signs

- 1994 | Sculpture, Sculpture, Sculpture

- 1993 | Tree artist show

- 1991 | Untitled

- OUTDOOR

- INFORMATION

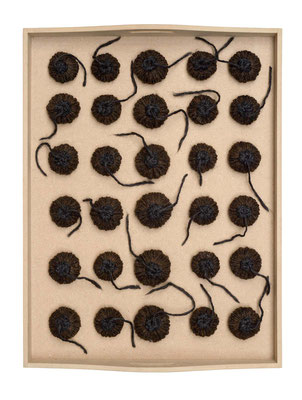

2017

32,2*32,5*19,5 cm

textile, mdf, paint. paper, steel

2016

MOTHER | MAMMA

2016 Mother, Summer Exhibition, M1 Gallery, Skagen, Denmark

2015

A BREEZE FROM THE SOUTH | SUNNLENSKUR BLÆR

2015 They, Gallery Ormur, History Center in Hvolsvöllur, Iceland

2013

THE OLD FARM, 101 REYKJAVIK | GAMLI BÆRINN, 101 REYKJAVÍK

2013 Under The Open Sky, Skólavörduholt, Reykjavik, Iceland

Work in two pieces: outdoor pedestal and indoors model

Model construction: Árni Þ. Sigurðsson

There once was a farmhouse that later was torn down ... long ago.

At the boundary of reality, dreams and memories the old farm still stands on the green hillside, with a view of the glacier, once under a clear sky but now as a model, indoors, in downtown Reykjavik. To protect it from the elements, the model which was intended to be placed outdoors, has been placed elsewhere.

The model was showed in Fiðluviðgerðir, Jónasar R. Jónssonar at Skólavörðustígur 16, 101 Reykjavik.

Verkið er í tvennu lagi módel og stöpull.

Smíði módels: Árni Þ.Sigurðsson

Einu sinni var sveitabær sem síðar var rifinn ... fyrir löngu.

Á mörkum veruleika, drauma og minninga stendur Gamli Bærinn ennþá í grænni hlíð með útsýni til jökulsins, áður undir berum himni, nú sem módel undir þaki í 101 Reykjavík.

Módelinu af Gamla bænum var ætlað að standa úti á stöpli en stendur nú annars staðar og Gamli bærinn er ekki heldur á sínum upprunalega stað, því hann endaði að hluta til í öðru húsi. Gamli bærinn var rifinn af sínum stað, það sama gæti hent módel á stöpli í miðbæ Reykjavíkur. Stöpullinn mun því standa án módels en á honum verða upplýsingar.

2012

SONG TREE | SÖNGTRÉ

130*190*130 cm (tree) + 35,8*42*35,8 cm (chair)

steal, wool, wood

2012-2019

2010-2014

BURCHA

2014 Not Quite Lysistrata, Art on Armitage, Platform Projects – Art Athina International Contemporary Art Fair, Athens, Greece

2010 Listveisla, Safnasafnið, Svalbarðströnd, Iceland

In my works, I have tried to revitalize various materials and objects that formerly served useful and practical purposes. Once things are in my clutches, a new reality awaits them and an entirely different role. I use objects that we handle daily, or things that are all around us but that we hardly notice because they are so evident. With aesthetics as my guide, I am trying to make use of them and give them new life. By recycling them, I attempt to ignite visions, memories, and ideas in the viewer.

Often these are mass-produced objects that have been sold all across the globe. Some of them are things that I find, some I buy, and some I receive as gifts. Often I take these objects apart, but others I can use whole, putting them together with different materials and trying to bring forth a new character. I ask myself why this thing is so popular, and why people continue to use it. Where does the idea come from that this is something that a person needs, and what branch of psychology tells us, for example, that Barbie dolls are good for little girls? What lies behind all of this mass production? Is it merely money? And if that is the case, what then comes in its place: what thing is it that we ''have to have'' when that has become obsolete? Where is mankind going with all of this consumption, and will it all be at the cost of our earth?

Character formation is a very delicate matter, one that can have the most unexpected consequences. Models are drawn from various directions, with influences both desirable and undesirable. Thus I considered how hats and neckties were, for a long time, indicators of respectability, while high-heeled shoes and dresses with plunging necklines were, and still are, symbols of woman-as-sex-object: something pleasurable to look at and, possibly even, get to touch.

Sometime, far in the past, men began to wear something resembling neckties. On Trajan's Column in Rome we may see a male figure with some sort of tie around his neck. In eighteenth-century America, a special neckcloth came into use, and this appears to be the origin of the wearing of neckties. But the necktie as we know it today was first worn in university faculties in Britain, as part of the student uniform. Nowadays, neckties are often worn on important occasions to emphasize

that the event, the place, and the moment are to be taken seriously.

When we look at clothing production, we notice that women's clothes have, generally, been designed by men, resulting in clothing that has, far too often, not been very convenient to wear or afforded good protection, and in which the wearers – women – have not felt good. Some women's apparel can even be positively dangerous, for example certain sorts of shoes. Women also design clothing for other women, often taking part in the production of demeaning clothes, something

which raises large questions. And it often appears that many think a woman looks best naked or scantily clad.

When Barbie dolls came into the world, a strange female image appeared that was obviously supposed to represent the look of the ''ideal woman'', at least in the opinon of certain section of the male population – a standardized female figure that such men imagined to be the perfect woman, providing a model for emulation by young girls. When I was a little girl, I played with dolls that looked like children or babies. The juxtaposition of these two, Barbie and a child, says much about the

indoctrination of our children. But now Barbie is out and other things are replacing her.

The question remains, though: why is there such a yawning gulf between our models of women and men?

Time passes and much occurs within its limits to which we are impervious, things that we forget to look at and define in our own way.

2010

THE TRAVEL | FERÐALAGIÐ

2010 Art on Armitage á SUPERMARKET, Kulturhuset (The House of Culture), Stockholm, Sweden

2008 Home, Start Art Gallery, Reykjavik, Iceland

2008

2008 BYE BYE ICELAND | BÆ BÆ ÍSLAND, Akureyri Art Museum, Akureyri, Iceland

2007

LIFE ON EARTH | LÍF Á JÖRÐU

2007 Start Art Gallery, Reykjavik, Iceland

NAIL SOUP | NAGLASÚPA

2014 Iceland: Artists respond to Place, Katonah Museum of Art, Katonah, NY, USA

2014 Iceland: Artists Respond to Place, Scandinavia House, American-Scandinavian Foundation, New York, USA

2007 Start Art Gallery, Reykjavik, Iceland

Working with man-made objects scavanged from the earth around rural farmlands, Þórdís Alda Sigurðardóttir (b. 1950) recombines these found artifacts with spools of thread, skeins of yarn, and bits of cloth to create assemblages that symbolize both the latent and spent potentiality of materials. In Nail Soup, a strange stew of spools and nails spill forth from an aluminum pot. The objects reference gendered roles of tending the home and working the land, and the essential need for clothing and shelter as protection against the elements. Þórdís’s title refers to a common Scandinavian folk story about creating sustenance out of nothing for the sake of survival.

Pari Stave

2005

2005, Gullkistan, Art Festival Laugarvatn, Iceland

2005 The North Atlantic Islands, The Copenhagen City Hall, Copenhagen, Denmark

2004-2019 |WAX|

Mixed media

36,6*36,5*4 cm | 37*37*2,5 cm | 48*48*4 cm

THREADS |2003-2017|

2003

2000

ORGASM | LOSTI

2000, Akureyri Art Museum, Akureyri, Iceland

1999

LAND | LAND

1999 Land, LÁ, Art Museum of Árnessýsla, Selfoss, Iceland

1997

1994

CORONATION | KRÝNING

HOMAGE A JÓN GUNNAR ÁRNASON | JÓNI GUNNARI TIL HEIÐURS

Living Art Museum (NYLO), Reykjavik, Iceland

SCULPTURES

1985-1990

1984

SCHOOL ARTWORKS | SKÓLAVERK